(2022) How Product Managers Use Senseshaping to Drive the Front-end of Digital Product Innovation, Research-Technology Management, 65:2, 29-40, DOI: 10.1080/08956308.2022.2014718

Digital product teams innovate in dynamic environments, in which they have incomplete knowledge and function under conditions of broad and diffused team membership and leadership. Generally, a product manager (PM) with no direct authority over the innovation team coordinates diverse cross-functional stakeholders to drive product innovation by initiating appropriate product and feature responses to key internal or external trigger events. This qualitative study of 83 such triggered digital product or feature responses, which the author interpreted through a sensemaking-sensegiving lens, revealed senseshaping—a dynamic, feedback-rich, contextual, and improvisational process the PM uses to build team understanding and commitment to action. The author presents five senseshaping practices PMs can use to help their organizations to recognize, interpret, and respond appropriately to new information, sensemaking cues, or unusual events in the front-end of digital innovation.

Companies in all industries are developing digital products in response to digital transformation (Joglekar and Nagaraj 2017; Venkatraman 2017; Weill and Woerner 2018; Nagaraj 2019; Mugge et al. 2020). These digital products may be pure software products, such as mobile applications, video games, and enterprise information systems; digitally enabled and connected physical products, such as smartphones, video game consoles, and credit cards with chips; or digitally enhanced traditional products, such as automobiles, clothing, refrigerators, and doorbells. These products could be for sale to customers or deployed internally to support customer-facing services, ecosystem relationships, and key operational processes.

Digital innovation teams face several challenges as they attempt to innovate. They frequently operate in unfamiliar and dynamic environments (Nylén and Holmström 2015; Lyytinen, Yoo, and Boland Jr 2016), and team members often lack the individual and shared knowledge required to collaborate and innovate (Carlile 2002; Lyytinen, Rose, and Yoo 2010). In situations of broad and diffused team membership and leadership, developing a shared understanding and converging on and committing to the right response to new information can be difficult. Digital product innovation teams comprise various stakeholders across functions and organizations with different perspectives and priorities. In addition to engineering, digital innovation incorporates several new functions such as user experience (UX) design, DevOps, customer success management, and ecosystem partner management (Van Alstyne, Parker, and Choudary 2016; Gnanasambandam et al. 2017). Digital innovation is often customer-centric and rapid feedback from the field is vital, which means that traditionally downstream functions like marketing and sales now become key stakeholders in the digital innovation process. Finally, digital products are often part of a larger digital ecosystem and therefore innovation also sometimes requires collaborating with external organizations (Chesbrough 2003).

The Product Manager Role

To drive product innovation, the product manager (PM) coordinates diverse stakeholders of digital innovation teams that often hold incomplete and differing perspectives and priorities (Bussgang, Eisenmann, and Go 2011; Horowitz 2014). A PM is generally an individual contributor who identifies market problems worth addressing; defines solutions, which could consist of new products or feature changes to existing products; provides requirements and market priorities to development teams that might use either waterfall, Agile, or hybrid methods; works with the marketing, sales, and ecosystem development teams to enable successful go-to-market; and continuously improves product-market fit. Ultimately, a PM is responsible for products and features meeting intended customer and business goals over their life cycle. Ironically, the PM bears this ultimate responsibility while having no formal authority over the necessarily diverse group of stakeholders involved in the innovation process.

Despite being saddled with accountability without requisite authority, the PM’s role is attractive and vitally important in the technology sector (Tsuchiyama 2011; Gellman 2016). Being a PM is often a stepping stone to senior leadership positions—Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella, the CEO of Google and Microsoft, respectively, are two examples of PMs who have rapidly ascended to the C-suite in the technology industry.

In response to the growing importance of the PM role, practitioners have created several experience-based and popular “how-to” guides for PMs (Pichler 2020; Olsen 2015). Scholarly research has focused on the “why” of product management and confirmed its importance in the innovation process (Koufteros and Marcoulides 2006; Rauniar et al. 2008; Tyagi and Sawhney 2010; Gaubinger et al. 2015); however, few scholarly studies have examined “what” the PM does to enable and drive digital innovation. This qualitative research study based on interviews with 26 digital PMs in the US, and theoretically framed by the sensemaking-sensegiving literature (Weick 1995; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005), attempts to partially address this gap in scholarship while simultaneously providing practitioners with evidence-based guidance on how to initiate digital innovation.

While PM activities generally span the entire innovation life cycle, this study focuses on the front-end of digital product innovation where the PM must define and initiate an orchestrated product response when confronted with key trigger events (sensemaking cues per Weick 1995). Such cues could be external (for example, changes in customer usage patterns, competitive feature introductions, and availability of new technologies and tools), or internal (for example, a new executive appointment). Specifically, the study seeks to answer the question: How does a digital product manager work with stakeholders to initiate an appropriate product or feature response to a trigger event?

This study illustrates that the PM applies a dynamic, feedback-rich, contextual, and improvisational process across the innovation stakeholder network to build team understanding and commitment to action. The author refers to this form of sensemaking-sensegiving as senseshaping.

Theoretical Framing

Sensemaking is the process through which individuals and groups recognize, interpret, and assign meaning to unusual cues (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005; Maitlis and Christianson 2014). Prospective sensemaking, a specific variant of sensemaking, answers the twin questions of “What’s going on?” and “What should we do about it?” (Weick 1995; Maitlis 2005; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005; Maitlis and Christianson 2014; Brown, Colville, and Pye 2015; Sandberg and Tsoukas 2015). Prospective sensemaking drives the acquisition of new knowledge, converges the different individual interpretations of that knowledge made by various team members, and catalyzes action in response to triggering events (Thomas, Sussman, and Henderson 2001; Calvard 2016). In product innovation contexts, researchers have found that such sensemaking improves product outcomes (Dougherty et al. 2000; Wright et al. 2000; Akgün, Lynn, and Yılmaz 2006; Akgün et al. 2012).

Sensemaking is difficult because it gets compromised either by a desire to normalize things away, which results in cues being ignored, or by preconceived schemata (models) and scripts that drive the wrong response (Weick 1993, 1995). Thomas, Sussman, and Henderson (2001), Maitlis and Christianson (2014), and Sandberg and Tsoukas (2015) summarize the practices used to address such biases and successfully respond to an event: (1) acquiring information with breadth, depth, and context from a diverse network of experts; (2) creating multiple interpretations through discourse with a different network of experts than those that acquired the information; (3) developing a shared perspective that can be codified; and (4) communicating the perspective with credibility using tools of persuasion to increase likelihood of action—that is, sensegiving.

Sensegiving by an individual, which scholars view as a variant or extension of sensemaking, aims to create meanings for the target audience (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005) and to explicitly influence stakeholders to accept the output of sensemaking (Gioia and Chittipeddi 1991; Tallon 2014). Sensemaking and sensegiving are thus viewed as discrete but related activities reflecting two sides of the same coin (Rouleau 2005)—the process of creating and subsequently acting on knowledge.

Sensegiving has the potential to “affect the sensemaker as well as the target” (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005, p. 416) through feedback from the target to the sensemaker (Weick 1979). For example, Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly (2016) outline how designers and marketers in cross-functional new product development teams, acting simultaneously as sensemakers and sensegivers, use feedback-driven practices to expand each other’s horizons and create shared meanings. They refer to this multiparty and feedback-rich form of sensemaking as resourceful sensemaking.

The concurrency of sensemaking and sensegiving and the feedback loops between them are particularly relevant to digital innovation contexts (Nagaraj, Boland, and Lyytinen 2017). The dynamic and fast-moving environment that a digital innovation team operates in allows little time between sensemaking and sensegiving. In a diffused leadership situation, innovation stakeholders do not passively receive “sense” (meaning) from a leader. Any attempt at sensegiving by any member of the group provokes feedback from other stakeholders with the expectation that the feedback will be acknowledged and acted upon by the sensegiver. Building on the concepts of prospective and resourceful sensemaking and sensegiving, in this study the author frames the PM as a concurrent sensemaker and sensegiver who creates shared meaning and aligned action across a diverse cross-functional stakeholder group without the traditional sensegiving authority of a top-down leader.

The dynamic and fast-moving environment that a digital innovation team operates in allows little time between sensemaking and sensegiving.

Method

The author used a constructivist grounded theory development approach informed by the literature (Charmaz 2014) to understand how PMs work with their cross-functional stakeholders to construct appropriate product or feature responses to unusual trigger events or sensemaking cues. The author invited 32 digital PMs from their professional LinkedIn network to participate in the study, and 26 accepted. The 26 participants—based in Northern California (19), Boston (5), Seattle (1), and New York (1)—are responsible for a variety of digital products (Table 1). The author used a semi-structured interview format based on the critical incident technique (Cope and Watts 2000) to extract 83 “vignettes” (episodes) from the PMs, with each PM contributing between 2 and 5 vignettes. Each vignette captured the actions the PM took after a trigger event to construct an appropriate product or feature response their team supported. The PM’s actions focused on the front-end of response formulation, not on the engineering development or go-to-market implementation activities. The vignettes covered a range of digital products (42 pure software products and 41 products with a hardware component). Although the author used a convenience sampling approach to secure study participants, the resultant sample of 83 vignettes provides a representative and rich view into the responses initiated by the PM.

Table 1. Summary of interviewees and vignettes

| PMs (26) | Experience Years as PM |

Companies (49) | Episode Vignette IDs (83) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <5 | Software | 1.1 Analytics platform A; 1.2 Analytics platform B; 1.3a/b: Middleware |

| 2 | 10–15 | Software | 2.1 Inbound logistics; 2.2 End-to-end suite; 2.3 Freight forward; 2.4 Report tool |

| 3 | 10–15 | System | 3.1 Telecom router; 3.2 Next gen “NFV” router; 3.3 Router software roadmap |

| 4 | 10–15 | System | 4.1 Automation equipment; 4.2 Next gen automation product; 4.3 Higher capacity automation product; 4.4 Regulation-driven product changes |

| 5 | 15+ | Software | 5.2a/b Energy efficiency and management product; 5.3 a/b Collaboration software for Product Line Management (PLM) market; 5.4 Mortgage loan origination software |

| 6 | 15+ | System | 6.1 Home theatre; 6.2 Premium speaker; 6.3 Headphones; 6.4 Tablet speaker |

| 7 | 15+ | Software | 7.1 E-Channel connector module on enterprise software platform; 7.2 Social extension to enterprise platform; 7.3 Installation settings on platform; 7.4 Sales experience enhancing toolset |

| 8 | 10–15 | System | 8.1 People tracking solution–A; 8.2 Robot-based medical telepresence; 8.3 Lung cancer treatment device; 8.4a/b People tracking solution reprioritization |

| 9 | 15+ | System | 9.1 Networking switch–feature A; 9.2 Networking switch–feature B; 9.3 Next generation “software defined networking” product |

| 10 | 10–15 | Software | 10.1 Video delivery Software-as-a-Service (SaaS); 10.2 Platform to deliver mobile connectivity service for Internet of Things; 10.3 Platform to push software updates in an enterprise |

| 11 | <5 | Software | 11.1 Integration SaaS; 11.2 Web developer kit; 11.3 Integration feature |

| 12 | 15+ | System | 12.1 Storage system for enterprise; 12.2 Storage system for clusters; 12.3 Disk-based backup service for enterprises |

| 13 | <5 | System Software |

13.1 Infiniband interface on chip; 13.2 Next generation “structured” chip; 13.3 “NoSQL” database product |

| 14 | 15+ | Software | 14.1 Product catalog and shopping guide for consumer; 14.2 New marketplace portal for sellers and buyers; 14.3 Mobile application for field service technicians; 14.4 Magazine-style front-end to search engine; 14.5 Social features on search |

| 15 | 10–15 | System | 15.1 Managed WiFi + Cellular base station; 15.2 Service provisioning framework for Internet Service Providers; 15.3 Enterprise-located, carrier-owned base station |

| 16 | 15+ | Software System |

16.1 Threat management product;16.2 Subscriber analytics product; 16.3 Chip for home router |

| 17 | 15+ | Software System |

17.1 Data Integration (DI); 17.2 Network appliance for bandwidth management; 17.3 DI release priority; 17.4 DI component |

| 18 | 10–15 | Software | 18.1 Antivirus agent for handset; 18.2 Enterprise security suite feature priority |

| 19 | <5 | Software | 19.1 “REST API” feature on billing platform; 19.2 Knowledge base product |

| 20 | 15+ | Software | 20.1 Enterprise IT security delivered as a SaaS product; 20.2 Solution to increase security of mobile devices |

| 21 | 5–10 | System | 21.1 Internet media streaming appliance; 21.2 High-end solid-state flash memory device |

| 22 | 10–15 | Software | 22.1 Advertising platform; 22.2 Advertising platform for small business; 22.3 Advertising platform “opt-out” feature |

| 23 | 15+ | System Software |

23.1 Video compression and delivery product for telecom service providers; 23.2 Traffic optimization product for telecom service providers |

| 24 | <5 | Software | 24.1 Network-based expertise discovery; 24.2 Video search within enterprise |

| 25 | 10–15 | System | 25.1 Software kit for WiFi; 25.2 Microcontroller (uC) chip; 25.3 WiFi + uC chip |

| 26 | 15+ | System | 26.1 Domain Name Server (DNS) networking product; 26.2 Enterprise security appliance |

Over a three-month period, the author conducted face-to-face or telephone interviews that lasted between one and two hours. The study’s theoretical (sensemaking-sensegiving) framing informed the interview structure and questions. To avoid availability bias and “top of mind” examples (Tversky and Kahneman 1973), the author contacted the participants a day before their scheduled interview to remind them to recollect memorable sensemaking cues they had reacted to in their PM careers. During the interview, subjects identified the trigger event or cue that required attention and discussed how they worked with their stakeholders to craft an appropriate product or feature response. The author recorded and transcribed all 26 interviews. The author also took 4–6 pages of handwritten notes during each interview and prepared a 2–3-page memo capturing vivid impressions within 24 hours of each interview. Following the principles of theoretical sampling (Strauss and Corbin 1990), the author used insights gleaned from the first few interviewees to inform discussions with subsequent interviewees.

Based on the PMs’ narrative, the author classified vignettes as successes (54 of 83) or as failures (29 of 83) (Table 2).

Table 2. Vignettes failures and successes

| Success or Failure? | Vignette IDs |

|---|---|

| Failure (29) | 1.3a, 2.2, 2.4, 3.1, 3.2, 4.2, 4.4, 5.2a, 5.3b, 5.4, 6.4, 7.1, 8.4a, 9.2, 9.3, 10.1, 10.3, 13.3, 14.4, 15.1, 15.3, 16.2, 16.3, 17.2, 17.3, 20.2, 22.3, 23.1, 24.1 |

| Success (54) | 1.1, 1.2, 1.3b, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 4.1, 4.3, 5.2b, 5.3a, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4b, 9.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, 13.1, 13.2, 14.1, 14.2, 14.3, 14.5, 15.2, 16.1, 17.1, 17.4, 18.1, 18.2, 19.1, 19.2, 20.1, 21.1, 21.2, 22.1, 22.2, 23.2, 24.2, 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 26.1, 26.2 |

Success implied that in the PM’s opinion, the team had responded to the sensemaking-sensegiving trigger event with the appropriate product or feature response, whereas a failure indicated that the team had responded to the trigger event with an inappropriate product or feature response. The author examined the 29 failures to understand the types and causes of failure (Table 3) and unpacked the 54 successes to identify the practices deployed by the PM to surmount these inhibitors (Table 4).

Table 3. Analysis of 29 failure vignettes

| Reason For Not Overcoming Bias | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Failure: Unable to acquire necessary knowledge (11) | Political or Affective Failure: Unable to overcome organizational or individual stakeholder concerns (18) |

||

| Innovation Bias | Status Quo Bias: Inappropriately maintaining status quo (15) | 2.2, 16.3, 23.1 | 1.3a, 3.1, 3.2, 4.2, 5.2a, 6.4, 9.2, 10.1, 13.3, 16.2, 22.3, 24.1 |

| Action Bias: Hastily taking wrong action (14) |

7.1, 8.4a, 9.3, 10.3, 14.4, 15.1, 17.2, 20.2 | 2.4, 4.4, 5.3b, 5.4, 15.3, 17.3 | |

Table 4. Senseshaping practices observed in 54 success vignettes

| Senseshaping Practice | Project Vignette IDs Exhibiting the Practice |

|---|---|

| 1. Constructing situational innovation stakeholder networks (35) | 1.1, 1.3b, 4.1, 4.3, 5.2b, 5.3a, 6.2, 7.2, 7.4, 8.1, 8.3, 8.4b, 9.1, 10.2, 11.3, 12.1, 12.3, 13.1, 14.3, 14.5, 15.2, 16.1, 18.1. 18.2, 20.1, 21.1, 22.1, 22.2, 23.2, 24.2, 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 26.1, 26.2 |

| 2. Bringing credibility and clarity to network interactions (42) | 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 4.1, 4.3, 5.3a, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 8.1, 8.3, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, 13.1, 15.2, 17.1, 17.4, 18.2, 19.1, 19.2, 20.1, 21.1, 21.2, 22.1, 22.2, 23.2, 24.2, 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 26.1, 26.2 |

| 3. Iteratively synthesizing interaction outcomes (43) | 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.3, 4.1, 4.3, 5.2b, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4b, 9.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, 13.2, 14.2, 14.3, 16.1, 17.1, 17.4, 18.1, 18.2, 19.1, 19.2, 20.1, 21.1, 22.1, 22.2, 23.2, 24.2, 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 26.1, 26.2 |

| 4. Planning the response in bite-sized chunks (21) | 1.2, 1.3b, 2.3, 7.3, 7.4, 8.2, 11.1, 12.1, 12.3, 14.3, 16.1, 17.4, 18.1, 19.1, 19.2, 20.1, 21.2, 22.1, 22.2, 24.2, 25.1 |

| 5. Operating within the organization’s formal decision-making framework (23) | 1.2, 1.3b, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 6.1, 6.3, 8.3, 8.4b, 9.1, 11.2, 14.1, 14.2, 17.1, 17.4, 18.1. 18.2, 19.1, 20.1, 21.1, 22.1, 22.2, 26.1 |

Subsequently, the author requested a small number of expert practitioners (other than the subjects) to provide feedback on the findings (Van de Ven 2007). Given the research method, the grounded theoretical perspective gained through this study should be viewed as having been “constructed” rather than as having “emerged” (Charmaz 2014).

Findings

The study revealed three main findings:

- The PM’s ability to craft an appropriate team response to a trigger event is hampered primarily by one of two innovation biases: status quo bias or action bias. These biases arise either from lack of knowledge or from organizational and individual concerns about the implications of the response.

- The PM attempts to overcome innovation bias by deploying one or more of five sensemaking-sensegiving practices with the aim of building required team knowledge and/or addressing organizational and individual concerns.

- The combination of practices used (not all practices are deployed in every case) results in senseshaping—a dynamic, feedback-rich, contextual, and improvisational process of building understanding and commitment to action across the innovation stakeholder network.

Senseshaping is a dynamic, feedback-rich, contextual, and improvisational process of building understanding and commitment to action across the innovation stakeholder network.

Finding 1: Innovation Biases (Status Quo and Action) the PM Must Overcome

The author’s analysis of the 29 (of 83) failure vignettes revealed two types of innovation biases. In 15 of the 29 cases, the team continued to maintain the status quo (status quo bias) when a product or feature change would have been appropriate, whereas in the other 14 cases, the team took a hasty product-related action when status quo or a different alternative would have been preferable (action bias). The teams succumbed to these biases for one of two reasons. In 11 cases, the team suffered from cognitive failure, which is the inability to acquire the necessary knowledge before having to act. In the other 18 cases, individual or organizational concerns resulted in political or affective failure, an inability to overcome organizational or individual stakeholder concerns even though the necessary knowledge was available to the team.

Status Quo Bias––Status quo bias is an unwillingness of the actors to deviate from existing product ideas, business models, organizational routines, and sense of identity. Individuals and organizations look at opportunities without full knowledge and often use frameworks that have served them well in the past (Audia and Goncalo 2007; Nag, Corley, and Gioia 2007). Even when required knowledge is available, organizations often remain “entrenched” (Dane 2010) and bound by their “core rigidities” (Leonard-Barton 1992) as they interpret new information using their “dominant logic” (Bettis and Prahalad 1995). For example, PM 6 (vignette 6.1) worked for an audio company whose brand is known for premium sound quality. Faced with the trend that consumers were listening to more music on portable Bluetooth devices, the team considered but ultimately rejected the opportunity to build new lower-fidelity tablet speakers because of perceived lack of fit between the portable technology and their traditional high-end engineering identity. The PM’s inability to overcome the status quo bias stemmed in this case not from lack of knowledge but from an extremely entrenched value system that emphasized great audio quality. PM 6 noted, “I think if we’d been okay with good enough audio, which is actually the biggest competitor of the company, then we could have come up with something that would’ve targeted tablets and been a success. We could have focused on ease of use and cool industrial design. I think the upside would have been greater than the perceived downside.”

Action Bias––Action bias is the tendency to hastily overreact to events, especially if the events are visceral. In such cases, the perceived urgency prevents organizations from acquiring new knowledge in time or results in an over-reliance on recent past experiences (referred to as the availability heuristic [Tversky and Kahneman 1973]). For example, PM 15, a founder of a startup targeting wireless service providers, missed a significant opportunity to innovate because of an inability to acquire new information. As PM 15 (vignette 15.1) explained, “We went to the virtual appliance model as it is traditional and more easily digestible by the carriers. In hindsight, a hosted model would have been the right place to start from the long-term perspective even though initial traction of it would have been slow. But I was more familiar with the carriers buying products one way. I felt there was no way that a carrier would accept a cloud hosted solution.” Sometimes political considerations and emotions drove action. Sunstein and Zeckhauser (2011) suggest that if an incident is perceived as a “fearsome risk,” political and emotional, rather than rational, considerations may dominate. For example, in vignette 5.4, PM 5’s team reacted to an investment banker pitch with existential haste because the CEO believed there weren’t many companies left in that rapidly consolidating market. In this case, PM 5 said, “The technology was crap. My recommendation was ‘No thanks.’ But the CEO decided he didn’t want to miss out. He thought it was riskier to do nothing. He went forward, and it was a disaster.” However, these innovation biases can be overcome.

Finding 2: Practices that Build Knowledge and Buy-in and Overcome Innovation Biases

The author’s analysis of 54 (of 83) success vignettes revealed that PMs deployed one or more of five senseshaping practices to acquire relevant knowledge and address organizational and individual concerns and thus overcome innovation biases (Table 5).

| Number of Senseshaping Practices Used Concurrently | Number of Vignettes Where Practice Was Observed | Project Vignette IDs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 13.2, 14.1, 14.5 |

| 2 | 12 | 3.3, 5.2b, 5.3a, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 8.2, 12.2, 13.1, 14.2, 15.2, 21.2 |

| 3 | 22 | 1.1, 1.3b, 2.1, 2.3, 4.1, 4.3, 7.2, 7.3, 8.1, 8.4b, 9.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 14.3, 16.1, 17.1, 19.2, 23.2, 25.2, 25.3 |

| 4 | 15 | 1.2, 7.4, 8.3, 12.1, 12.3, 17.4, 18.1, 18.2, 19.1, 21.1, 22.1, 24.2, 25.1, 26.1, 26.2 |

| 5 | 2 | 20.1, 22.2 |

Constructing situational innovation stakeholder networks

In 35 of the 54 successful vignettes, PMs took a broad view of the “innovation team” and constructed a relevant and often eclectic network of diverse stakeholders in response to the triggering event. Reflecting upon the value of a network, PM 23 (vignette 23.2) said, “There’s a tendency when you’re a young and foolish product manager to want to do everything yourself, that I don’t need help. As time goes on you realize that getting insights from others and getting help from others, and talking things over with others is not a weakness.”

The author found PMs were strategic in constructing the required network—aware of the position, caliber, and value-add of each participant. While certain types of individuals were almost always included—for example, analysts from leading market research firms who were viewed as bearers of contextual and generally useful information and as market influencers—network membership was also situation specific. For example, looking to drive a security software product’s redesign triggered by an acquisition and facing internal resistance as a new PM in that organization, PM 26 purposefully included many customers and distribution channel stakeholders in his network because of the organization’s sales-driven culture. PM 26 (vignette 26.2) said, “If you don’t have the amount of customers, then you run into problems. You really need to muscle your way into customer calls. I met during that one-and-a-half year roughly, it was about a hundred customers and probably about 50 channel partners.” The author found other examples of situational member inclusion: PM 12 included a key supplier in his network (vignette 12.3) who possessed unique knowledge that would address a major roadblock to action that the team was facing; and PM 25 included a key customer prospect (vignette 25.2) whose perspective would reframe stalled team discussions.

Bringing credibility and clarity to network interactions

In 42 of the 54 successful vignettes, the PMs explicitly identified the importance of information credibility and clarity in creating team knowledge and securing buy-in. The perceived credibility of new information was related to the credibility of the PM bearing that information. PM credibility stemmed from personal attributes (personal credibility) or through strategic association (reflected credibility). PM 1 (vignette 1.1) said, “I spent a lot of time getting classifications that not a lot of people have. That means that I’m uniquely able to talk to particular users. In conversations with the engineering team, that communication just trumps everything else.”

Product managers’ credibility stemmed from personal attributes (personal credibility) or through strategic association (reflected credibility).

When PMs realized that their personal credibility was not strong enough to overcome status quo bias, they carefully chose and introduced credible new players or artifacts (objects such as prototypes, key design documents) into the stakeholder network to further advance their point of view. These objects support the PM in making their case as do persuasive validation sources, which could be customers, outside experts, standards bodies, well-respected colleagues, board members, or even documents and prototypes. For example, PM 13 (vignette 13.1) successfully prevented his organization from overreacting to a new industry standard by highlighting the actual specification document produced by the external standards committee: “600 or close to 700-page spec, and I printed it. I said this is the spec that has come out and it’s not even finalized yet. He looked at it and said, ‘This is never going to work because of the complexity of it.’” PMs also brought in outsiders with credible expertise to nudge their organizations to action when faced with entrenched positions. Having established credibility, the author found PMs used language and artifacts skillfully to ensure clarity and understanding.

Iteratively synthesizing interaction outcomes

In 43 of the 54 successful vignettes, PMs constantly compared and integrated stakeholder inputs to build knowledge and address individual and organizational concerns regarding action. Interactions with stakeholders helped identify gaps between the emerging product response and stakeholder concerns. Comparison and integration allowed the PM to evolve the product response to bridge the gap and create buy-in through subsequent interactions. PM 20 (vignette 20.1) said, “First and foremost, you look at the macro trend. The second thing that you do is you sit down with somebody like the engineers. The third vector that you do is you go and talk to several customers who are thinking ahead of everyone else. When you create a blend of these three vectors, you come up with some of the hypotheses that you want to go and test on the market. It has to be very interactive.”

Articulating the response in bite-sized chunks

In 21 of the successful vignettes, PMs articulated their desired long-term product response in bite-sized chunks. This approach focused the team on the more immediate time horizon and minimized uncertainty, thereby enabling more rational and open-minded participation in the knowledge cocreation and buy-in process. Chunking reduced the impact of uncertainty in three ways: plans became more understandable and measurable; decisions could be reversed if assumptions turned out to be incorrect; and a bounded response provided the PM with greater flexibility in reacting to and accommodating inevitable changes. For example, as PM 2 was conceiving a new paperless logistics platform for manufacturers (vignette 2.3), he encountered resistance from several “old school” colleagues. PM 2 said, “We might have got it halfway developed and completely failed. But I think breaking it into a bite-size plan that people could understand was helpful because this is something that I could present and people could understand that if we did Phase 1, we could probably get one customer.”

Operating within the organization’s formal decision-making framework

In 23 of the 54 successful vignettes, PMs took advantage of regularly scheduled and formalized decision review mechanisms or created new ones to mitigate anxiety and create time to build required knowledge and address concerns. The understanding that a scheduled and formal decision review point was around the corner allowed decision makers to not rush to interpretation and action when faced with a visceral external event. They could wait to develop new knowledge more diligently before coming to a conclusion at the scheduled decision review. Moreover, the use of regularly scheduled reviews assured stakeholders that wrong decisions or unworkable solutions could be more easily identified and rolled back. PM 17, who was faced with the unexpected end-of-life of a key component, highlighted the benefits of taking advantage of an organization’s decision-making cadence. PM 17 (vignette 17.4) said, “I thought he [the CEO] was overreacting and I thought other people were going along with the over-reaction. But we didn’t resolve it right then and there. We would settle it for sure at the next product committee meeting. It’s a standing meeting once a month.”

Finding 3: Senseshaping—the Dynamics of Practice Deployment

PMs concurrently deployed one or more of the five sensemaking-sensegiving practices in the 54 successful vignettes, with a typical vignette showcasing three practices on average. The process of deploying these practices was dynamic, feedback-rich, contextual, and improvisational. That is, in each vignette, the choice of which of the five practices to deploy and how was contingent on contextual factors such as the nature of the trigger event, the company’s maturity and its current business circumstances, the PM’s experience level and confidence, the degree of involvement by top management like the CEO, and so on. These factors were evident at different times, often in unexpected ways, even as the PM used the practices. The dynamic interaction between the stakeholders, the practices used, and the contextual factors impacted the trajectory of actions, how and when gaps in team understanding got closed, and when buy-in to collective action was achieved.

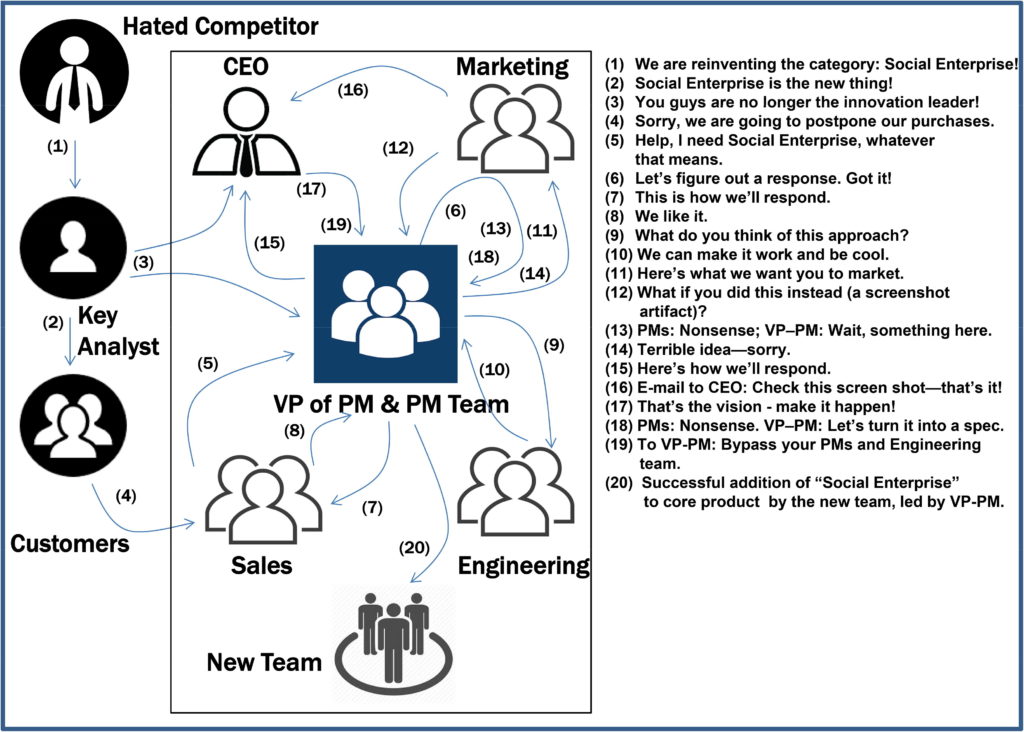

The 54 vignettes showed tremendous variation in the dynamics and consequent trajectory of senseshaping. We present vignette 7.2 with a stylized and simplified narrative map to illustrate the idiosyncratic dynamics of senseshaping (Figure 1). In this vignette, situated at an industry-leading and hyper-aggressive enterprise software company, the CEO’s anger at an unexpectedly unfavorable analyst comment triggered the PM and the product team into action. As the action commenced, the experienced PM deployed three of the five practices to orchestrate a suitable product response—building an appropriate network (practice 1), bringing clarity to stakeholder interactions (practice 2), and engaging in constant synthesis (practice 3)—while struggling to incorporate the CEO’s continued involvement and the unexpected inclusion of new players. Eventually they reached a satisfactory resolution, but the constructed response was unexpected.